“Brexit is only happening because Great Britain no longer wanted to be chained to a club of losers.“ (Clemens Fuest)

A celebration for the EU was held in Rome as the European project turned 60. However, the EU is in bad shape. It has been shaken by crises. Economic integration stagnates. Growth is plodding along. The (youth) unemployment rate is persistently high. The only ones still spinning yarns about a political union are the five presidents (here). The rifts between north and south, east and west are growing (here). With Britain, the first country is already leaving the EU. The unthinkable is occurring: the process of integration in Europe has become reversible. Europe is a project subject to revocation. Â Realignment is necessary in order to save it. In the wake of the Brexit shock, the EU Commission has responded as well. In a White Paper, they ask how Europe will look in ten years (here). They put five scenarios up for discussion, and do not explicitly advocate for a particular alternative. Nevertheless, their preferences are clear. It would be best for the EU Commission if Europe were to decide in favor of the great qualitative integration leap into a political union.

The European Idea

European integration was a response to a dark period in Europe: lack of freedom in fascistic regimes, the horror of two world wars, and economic hardship for broad swathes of the population. The dream of the fathers of the EEC was a democratic and constitutional Europe that lives in freedom, peace, and prosperity. To them, this seemed most readily achievable in a politically united Europe. Border barriers in Europe were to be a thing of the past. The external security of its members was to be guaranteed. Ultimately, Europe was to become the third global political power alongside the US and the Soviet Union. An economically integrated Europe was supposed to encourage political integration. Integrated private markets create material prosperity, promote democratic developments and make it difficult for terrible wars to occur. Economic integration was meant to be used as a driver of political unification.

Ideas about how to integrate economically were, however, of questionable character in the early days of the ECC. A broad majority of the policy adhered to the idea of “integration from above“. Markets were to be integrated via central market regulations. The markets for coal, steel and agricultural products were the most prominent victims. Market, competition, and subsidiarity fell by the wayside. These elements only gained acceptance through a change in the integration strategy. The 1992 Single Market project was a milestone for “integration from below“. Market regulations would no longer dominate. Goods and factor markets were to be opened, obstacles and barriers removed. The central element was the four fundamental freedoms of goods, services, labor, and capital markets. As a further element, the ECJ sustainably strengthened the power of competition with the “Cassis de Dijon“ decision.

In Europe it was agreed at the outset that economic integration was to be followed by political integration. Integrated economic markets were to promote a political union. The hope was that those who work together economically will also more often act together politically. However, this is anything but simple (here) in a Europe with heterogeneous social models (“Four Worlds“). Â One issue in a Europe that cooperates more closely politically is the question of what belongs to the market and what to the government. In times of market regulation, the state dominated as the coordinating agent. Many dreamed of a common European social model with far-reaching centralized competences in Brussels. With the 1992 Single Market project the market gained the upper hand. The competition of the social models was to be intensified, and the national leviathan to be disciplined. The latter, at least, was not successful.

The great line of political unification has been controversial since the beginnings of European integration. Some strive for a federal state. The goal is a “United States of Europe“ (Winston Churchill) (here). Classical separation of powers and competitive federalism would be key elements. This is hardly possible in a large heterogeneous entity without a common European public sphere. This variant is not currently up for discussion. The national governments are not ready to relinquish even more sovereignty. The opposite is the case. They claim back more of their sovereignty from Brussels. A majority of them are willing to accept a loose confederation at most. Within this structure it is also difficult to install the principle of separation of powers and to distribute competences clearly. There is a high risk that everyone will have their hands in each other’s pockets and the centralization in Europe will progress even further. The current EU is such a case. This cannot, as Thomas Apolte recently explained, go well (here). And it isn’t going well.

The Harsh Reality

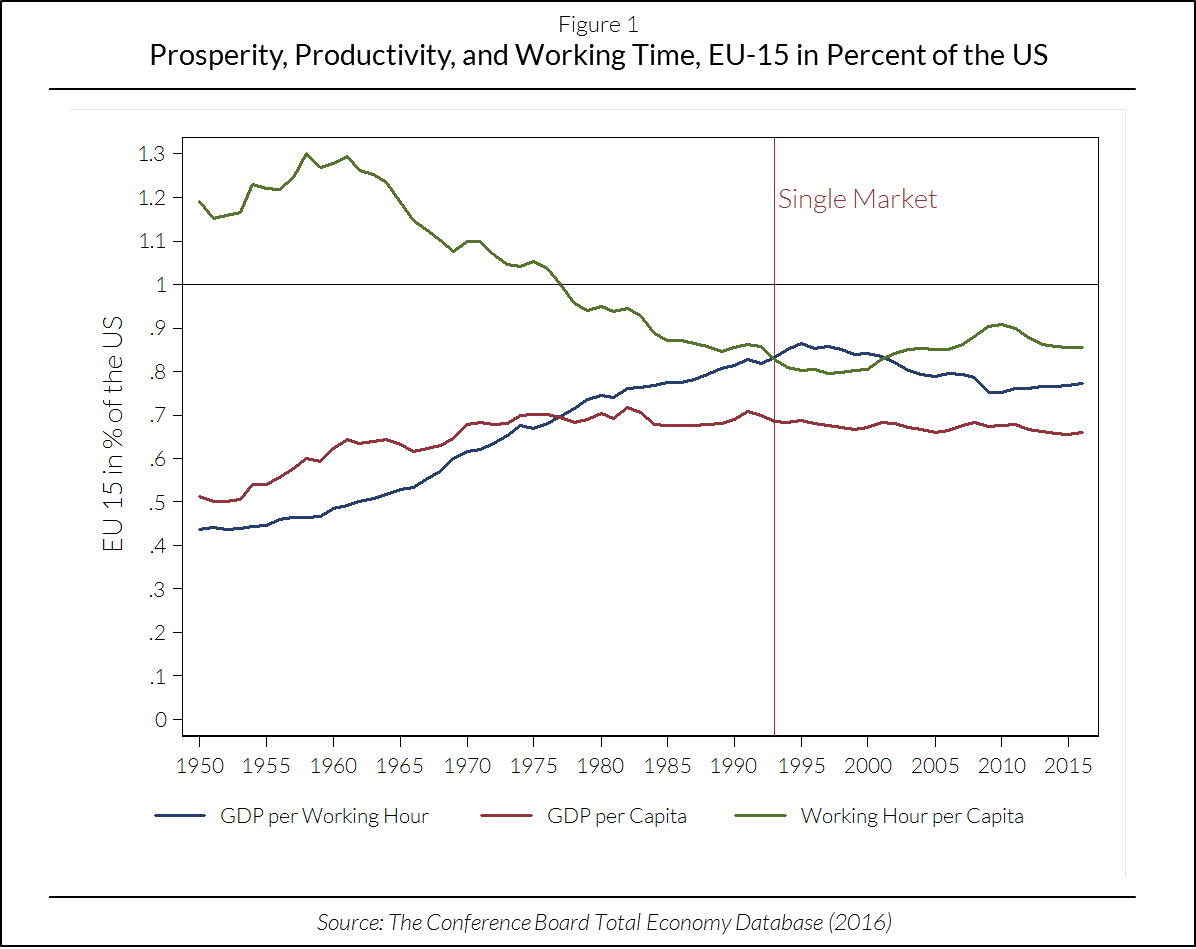

The process of European integration is faltering. 1) The EU is experiencing a growth crisis. All wealthy countries must deal with this problem. However, a comparison with the US shows that Europe is doing worse. Three things are particularly striking: firstly, the European per capita GDP has been below that of the USA since 1950. Since the middle of the first oil price crisis, it has stagnated at about 70% of American per capita GDP. The European single market couldn’t change this either. Secondly, since the mid-1990s Europe has increasingly fallen behind the United States with regard to the most important driver of growth, productivity per unit of labor. In the run-up to the 1992 Single Market project this was not yet the case. Thirdly, from the mid-1970s until the mid-1990s the European catching-up process in labor productivity was overcompensated by significantly higher unemployment in Europe. Europe has also been experiencing an unemployment problem since the oil price crisis, in the South more so than in the North.

– zum Vergrößern bitte auf die Grafik klicken –

Growth in Europe is weaker than it is elsewhere. Productivity is growing at a slower rate, and employment rates are falling more strongly. More open goods and factor markets could help to relieve this situation, but Europe takes this path increasingly less often. The elation of the “four fundamental freedoms“ has faded away (here). The enraged citizens set their sights on competition with increased frequency. National interest groups often successfully fight hand in hand with the government against the reduction of private market barriers, government regulations, public subsidies, and state monopolies. The bureaucracy in Brussels reinforces anti-competitive activities. It often places further regulatory shackles on economic agents. The worst, however, is the anti-competitive development in the European labor markets. National collective bargaining cartels segment labor markets, exclude (adolescent) employees and discriminate against less qualified unemployed individuals. Active labor market and sociopolitical aid is provided by (national) politics.

2) The most serious crisis currently, that which brought Europe to the brink of collapse, is undoubtedly the euro crisis. With the euro, the EU has taken a major, risky integration policy leap. It has turned integration on its head. Until the integration of the euro, the vast majority of economists believed that real economic integration comes before monetary integration. With the EMU, some of the members of the EU have reversed this order. The euro was introduced despite the existence of a fragmented domestic market. The second step was taken before the first. This could not go well, nor has it. The idea that a single currency would accelerate the process of real economic integration has proved to be wrong. The opposite has occurred. The EMU crisis has damaged real economic integration. Most notably, capital markets were once again strongly re-nationalized. The euro has done political integration a disservice.

The euro in its present form has failed because the member countries do not follow its rules. The architecture of the EMU is simple: monetary policy is centralized. All other economic policies are nationally organized. The autonomous national fiscal policies are limited (here). This has two consequences: The EMU is bound by rules and oriented towards stability. And the collective bargaining parties must bear the main burden of adapting to exogenous shocks. The crises of the EMU (banking, sovereign debt, and balance of payments crises) arose because banks, governments, and collective bargaining partners did not adhere to the explicitly and implicitly agreed upon rules. A multiple “moral hazard“ dominates: the actions and liability of private and state agents fall apart (here). There are two reasons for this: Member states are not willing to accept the loss of sovereignty

The Future Integration

The interesting idea of arriving at political unity via greater economic integration has proved to be an illusion. The process of economic integration has also stalled because it is becoming more difficult to keep markets open. “Market, competition, and subsidiarity“ are increasingly frequently supplanted by “government, cartels, and centralization“. Thus, an important driver of political integration is missing. However, political integration also encounters growing resistance. The EU has thus far not succeeded in satisfactorily accomplishing many of the tasks assigned to it by the countries. The permanent crises testify to this fact. One reason for this is serious legitimacy and solidarity deficits (here). Both can be better resolved at a decentralized level. It is therefore no surprise when demands are made for competences to be shifted back to countries and regions. The 5th scenario in the EU Commission’s White Paper, the great integration policy leap (political union), can thus be safely forgotten.

The EU will only continue to develop economically and politically if it succeeds in keeping the motor of economic integration running. This makes it necessary to once more unearth the buried sources of economic growth. The best medicine is more intense competition. The heart of economic integration is the European single market. It is anything but perfect. More work remains to be done. It therefore makes a good deal of sense to strengthen the 2nd scenario (“focus on the single market“) of the EU Commission’s White Paper. The EU must remove the many remaining obstacles and barriers in goods and factor markets. There is still much to be done in the services sector in particular. The labor markets are also in quite a sorry state. However, it is not just the EU Commission that must take on this challenge. Many regulations in the labor markets and in the social realm are national. This is why the national governments in particular have to complete their unfinished homework. They are shirking their responsibilities.

The landscape of economic and political integration in the EU has changed considerably over the last 60 years. Europe has become more heterogeneous. The successive extensions have been accompanied by an increase in the diversity of formal and informal institutions. The Tufts economist Enrico Spalaore put it like this: “A European Federation would be quite heterogeneous by most measures (ethnic, linguistic, cultural) and likely to face significant political costs when choosing common public goods und policies at the federal level. “ (here). A strategy of integration that measures everything by the same yardstick no longer does the diversity of the members justice. With a “Europe of multiple speeds“ and a “Europe à la carte“ there are integration policy alternatives (here). The core of both is the single market as an “acquis communautère“. In the first case, all pursue the same integration goals. The members differ only in how fast they want to achieve them. They strive for a federal political union.  In the second case, they aspire to different objectives. They select the areas in which they want to cooperate with which members, either permanently or only temporarily. The misleading idea of a political union in Europe is rejected, and quite rightly.

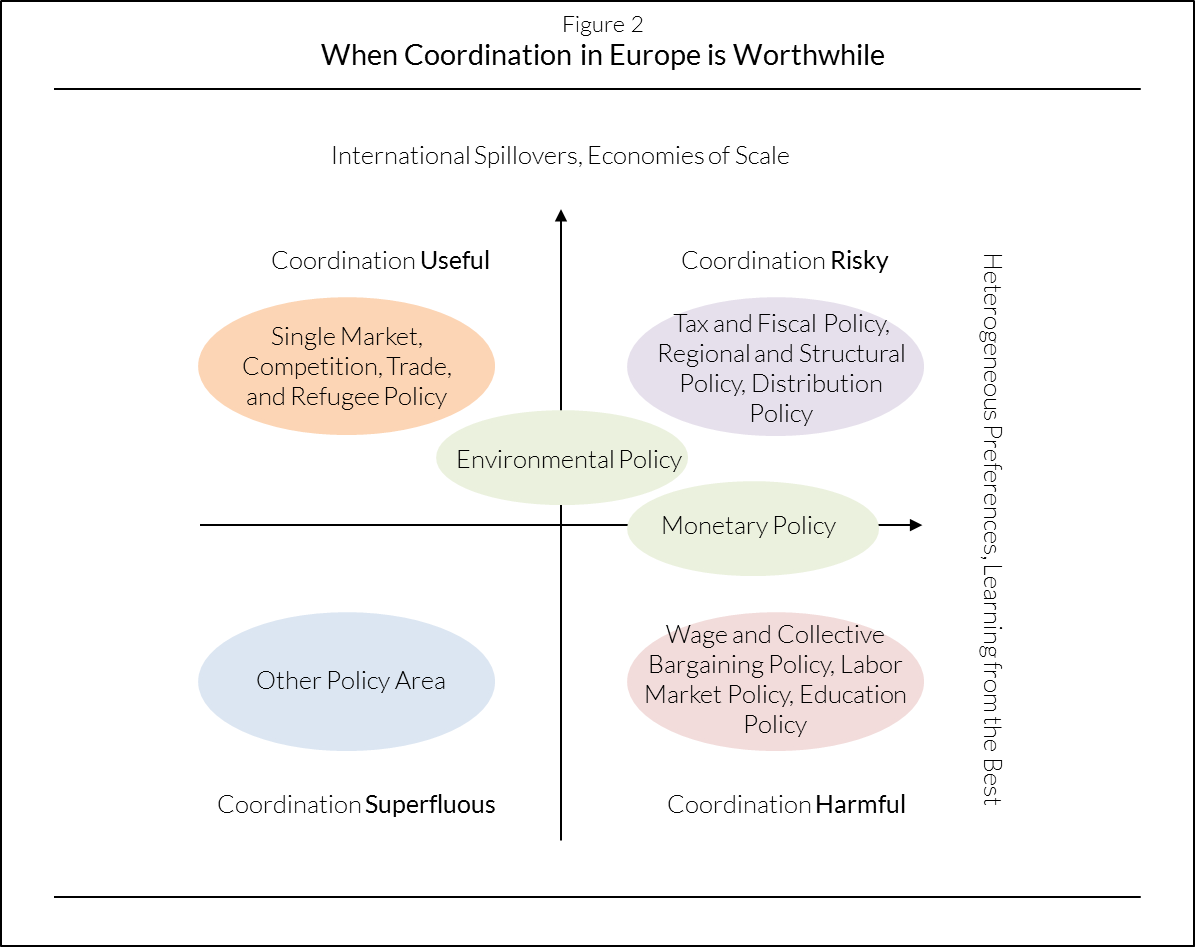

Whatever direction the integration policy of the EU takes, vertical competences must be clearly distributed. So far, the principle of subsidiarity is only an empty word. The economic theory of fiscal federalism provides clues as to how to breathe life into it. Significant economies of scale and regional spillovers argue for centralized solutions, heterogeneous preferences and learning from the best for decentralized ones (here). Which way the scale tips changes from one economic policy to another. It is clear that the more homogeneous the members are, the more likely it is that centralized solutions make sense. This is truer for smaller clubs of the willing than it is for larger ones. It is clear that the core of centralized activities comprises the single market and trade policy, but also the issue of refugees. In all other fields of economic policy, coordination of national activities is either harmful or at least risky. The EMU falls into the latter category, if it is not re-dimensioned and thus remains as heterogeneous as it has been so far.

– zum Vergrößern bitte auf die Grafik klicken –

Conclusion

The fate of the EU hangs in the balance once again. Legend has it that Europe has always emerged stronger from a crisis. This won’t always be the case. The EU is heading for multiple policy failures with the growth, unemployment, euro, and refugee crises. Now with the Brexit, it is clear that Europe has become a project subject to revocation. The collapse of the EU would be the end of the European dream of “peace, freedom and prosperity (for all)“. There is no more time to waste. Integration policy must seek a new course.  Europe must remember the elements that made it economically great: “market, competition and subsidiarity“. The hard core was and is the single market. The most important thing is to further develop it competitively. And a new strategy of European integration is needed. To lump all integration policy together is a foolish idea in an increasingly heterogeneous Europe. The great qualitative leap forward, a political union, belongs to the realm of integration policy fairy tales. A “Europe à la carte“ is the appropriate answer.

Hinweis: Das ist die englische Version des Beitrages „Europäische Union auf Widerruf? 60 Jahre und (k)ein bißchen weise“. Michael Labate hat den Beitrag übersetzt. Herzlichen Dank!

- Kurz kommentiert

Aufstand der 18

Inter-generative Verteilungskonflikte ante portas? - 27. November 2025 - Seltene Erden: Das „neue“ Öl?

China ist der Elefant im Raum - 22. November 2025 - Europäischer Emissionshandel in der Kritik (1)

Klima im Wandel

Wende in der (europäischen) Klimapolitik? - 8. November 2025